Central bank liquidity runs post-GFC financial markets

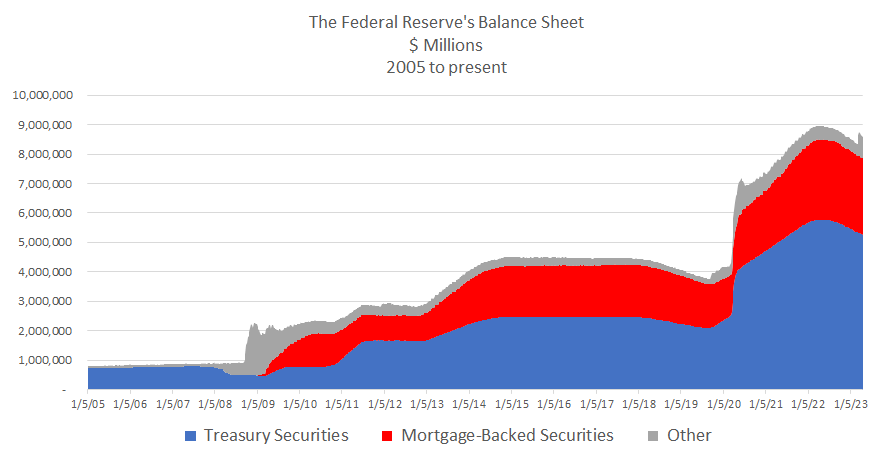

A lot changed in 2008/2009 after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). In addition to new banking laws and a zero interest rate policy, the Fed, followed by its global central bank counterparts, ramped up its balance sheet (buying MBS and treasuries) to calm financial markets and stimulate the economy with liquidity. Since the Fed pays for these assets with money that doesn’t exist, it effectively creates new money. This is widely known as “quantitative easing” (QE), and more colloquially known as “money printing”. Although QE has been used before (in the US during the Great Depression and in Japan during the early 2000s), the magnitude of central bank asset buying post-2009 has been unprecedented.

Net liquidity

Liquidity is the flow of cash and credit through financial markets. Although money supply has historically been the metric used to describe liquidity, the modern financial system has become a lot more complex over the years, adding additional financing vehicles and mechanisms. Money supply is still relevant for the real economy, but liquidity has become much more relevant for financial markets.

To see the full extent of central bank liquidity, economists have come up with “net liquidity”:

Net liquidity = central bank balance sheet - treasury general account (federal government bank account) - reverse repos (temporary collateralized bank loans)

While central bank balance sheet moves make the headlines, you must also subtract the treasury general account (red) and reverse repos (yellow) to calculate net liquidity (green), which more precisely measures funds that can freely flow through markets (treasury general account and reverse repos cannot).

Why is liquidity the focus?

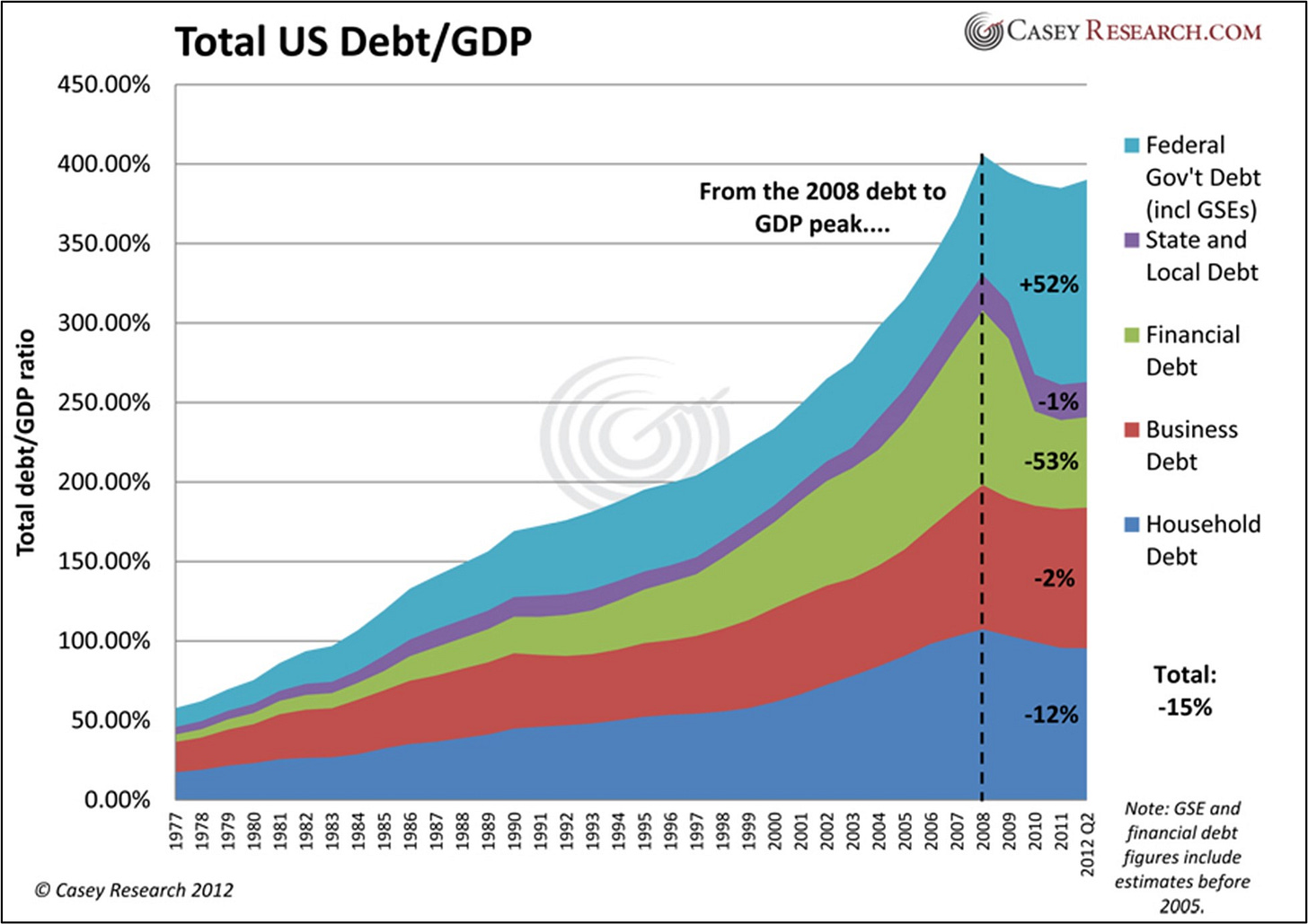

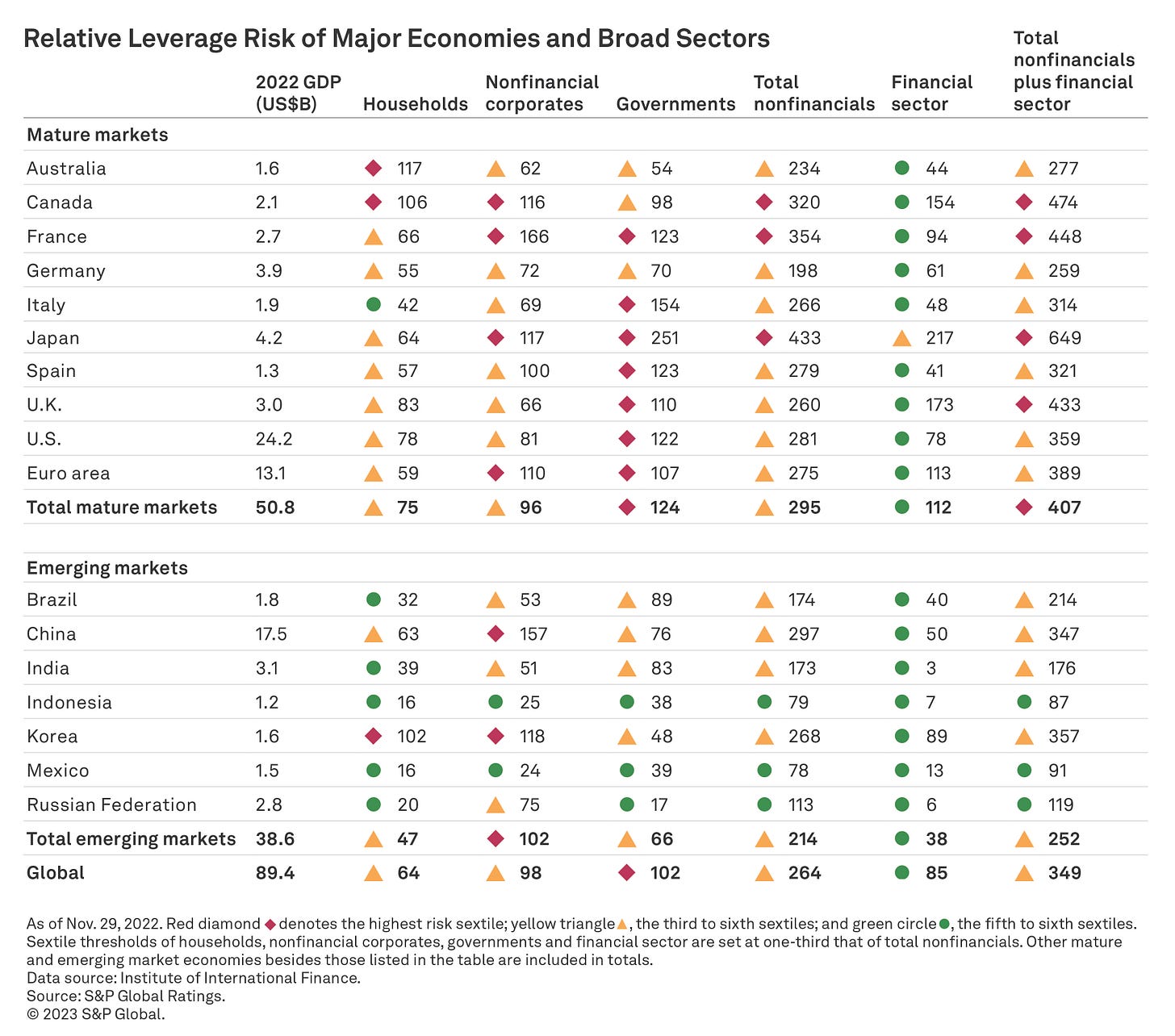

Global debt has surged since the GFC, accelerated by the pandemic, and today sits closer to $350T, with an average maturity of 5 years.

This means $70T in debt must roll over each year! You need balance sheet capacity in order to do so, a measure of liquidity, which is why it has become the most important factor in the markets today.

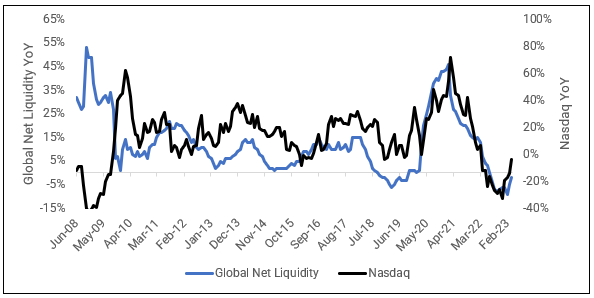

As illustrated below, global net liquidity from the largest central banks (US + China + Europe + England + Japan) has exploded since the GFC:

Since 2009 nothing has correlated more with markets, especially tech stocks and crypto, than global net liquidity. Why? Net liquidity growth is essentially monetary debasement, which benefits long duration assets (tech stocks) and monetary hedges (crypto).

Forget interest rates, GDP growth, inflation, etc. — liquidity has become the only game in town, the only economic force driving markets. It doesn’t matter if rates are 0% or 10%, central banks will refinance regardless to avoid default. They will do anything in their power to keep sovereign debt markets functioning.

Where does liquidity go from here?

Its clear net liquidity now controls markets — so where will it trend over the next 12-24 months? From the end of Q2 2021 to the end of Q3 2022, global net liquidity was in free fall as central banks around the world attempted to tame rampant inflation by tightening money supply (sucking out liquidity from the system).

However, since the end of September 2022, the global trend has reversed, mostly a result of the QE policies in China and Japan, as well as the US Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) launched in March in response to the regional bank crisis.

China and Japan have pumped liquidity into the market of late:

BTFP in the US pumped the Fed’s balance sheet in March ($ in millions):

Can the trend continue up?

I think it has to — lets focus on the US first.

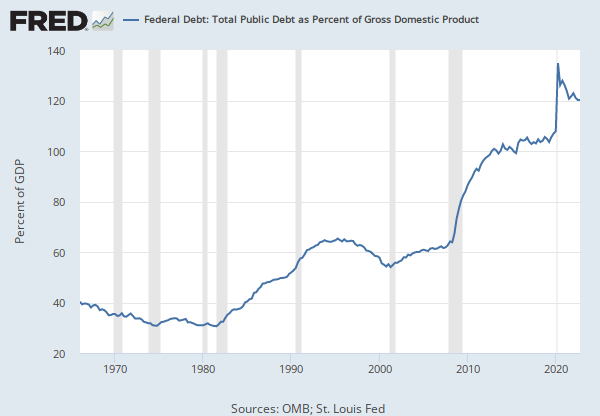

Its no secret we have a large debt problem. Since the GFC much of the debt has shifted from private sector to the federal government, which now has a debt/GDP ratio of 122%, the highest since WWII.

From 2009 to 2021 this wasn’t a huge issue. Interest rates were low so debt servicing was manageable.

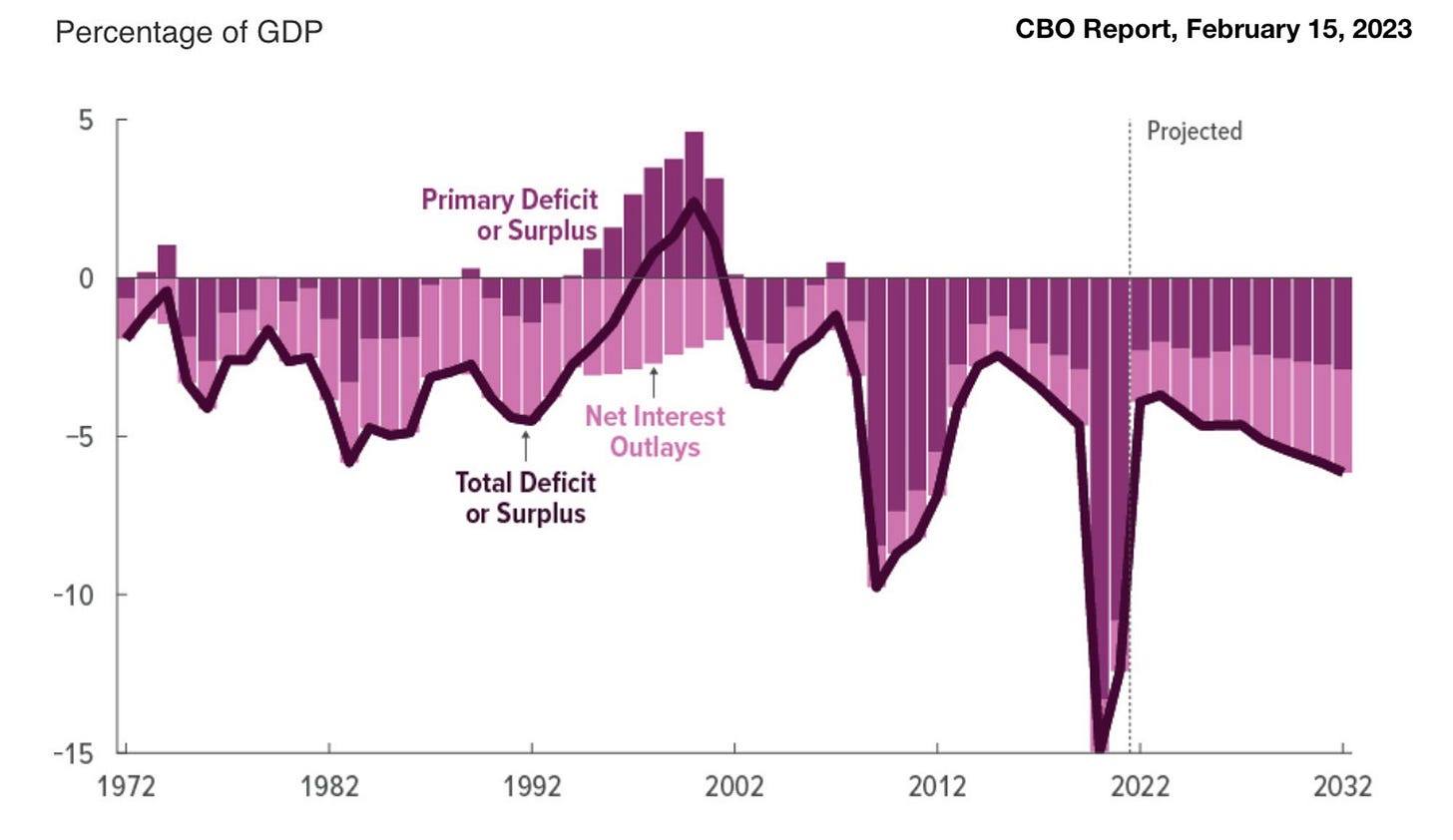

But with rates at the highest levels post-GFC, annual interest expense has begun to skyrocket. We already run large annual budget deficits (maroon), with ballooning interest payments (pink) we have a serious problem mounting.

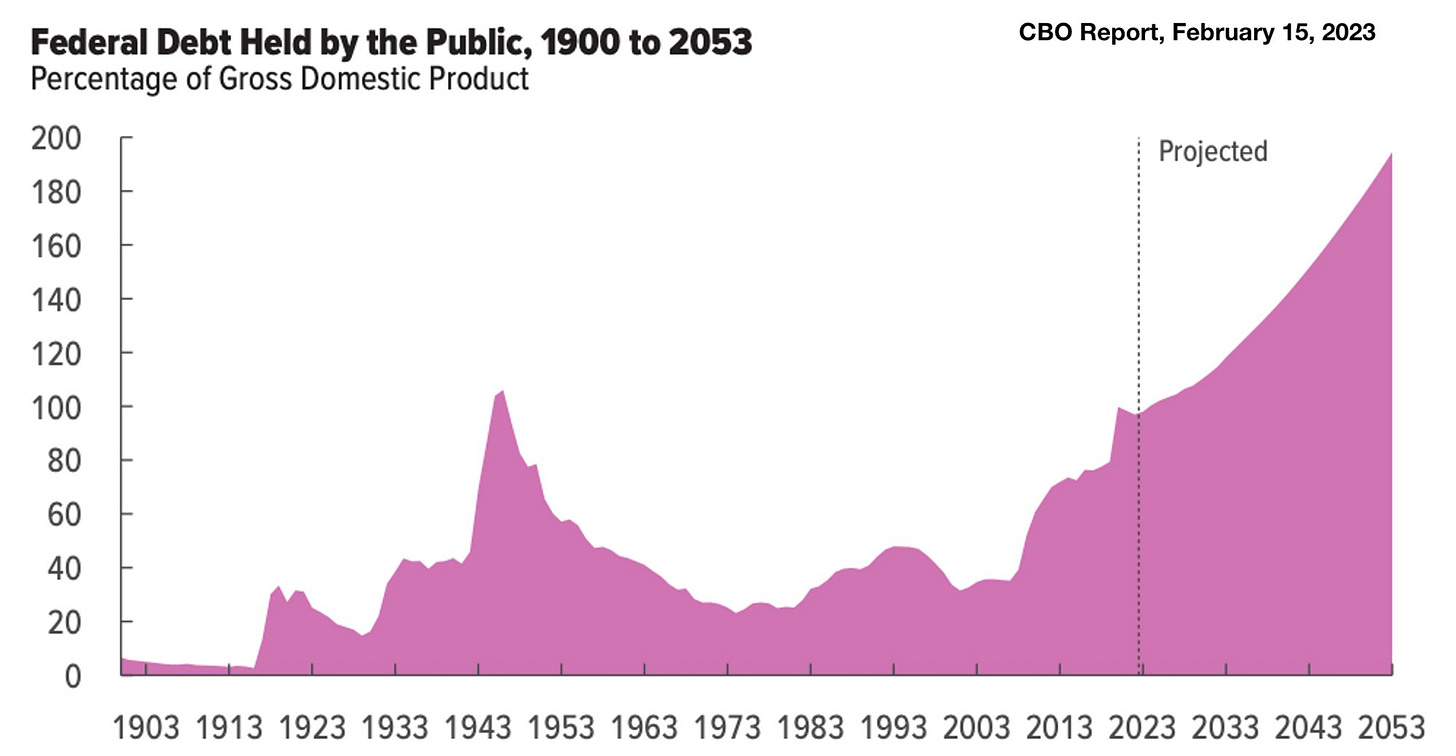

Because of our aging demographics and declining labor productivity, accelerating revenue (GDP) growth will be extremely challenging. The only way the federal government can realistically service their debt is by issuing more debt. The Congressional Budge Office (“CBO”, the non-partisan federal agency that provides economic and budget information to Congress) understands this:

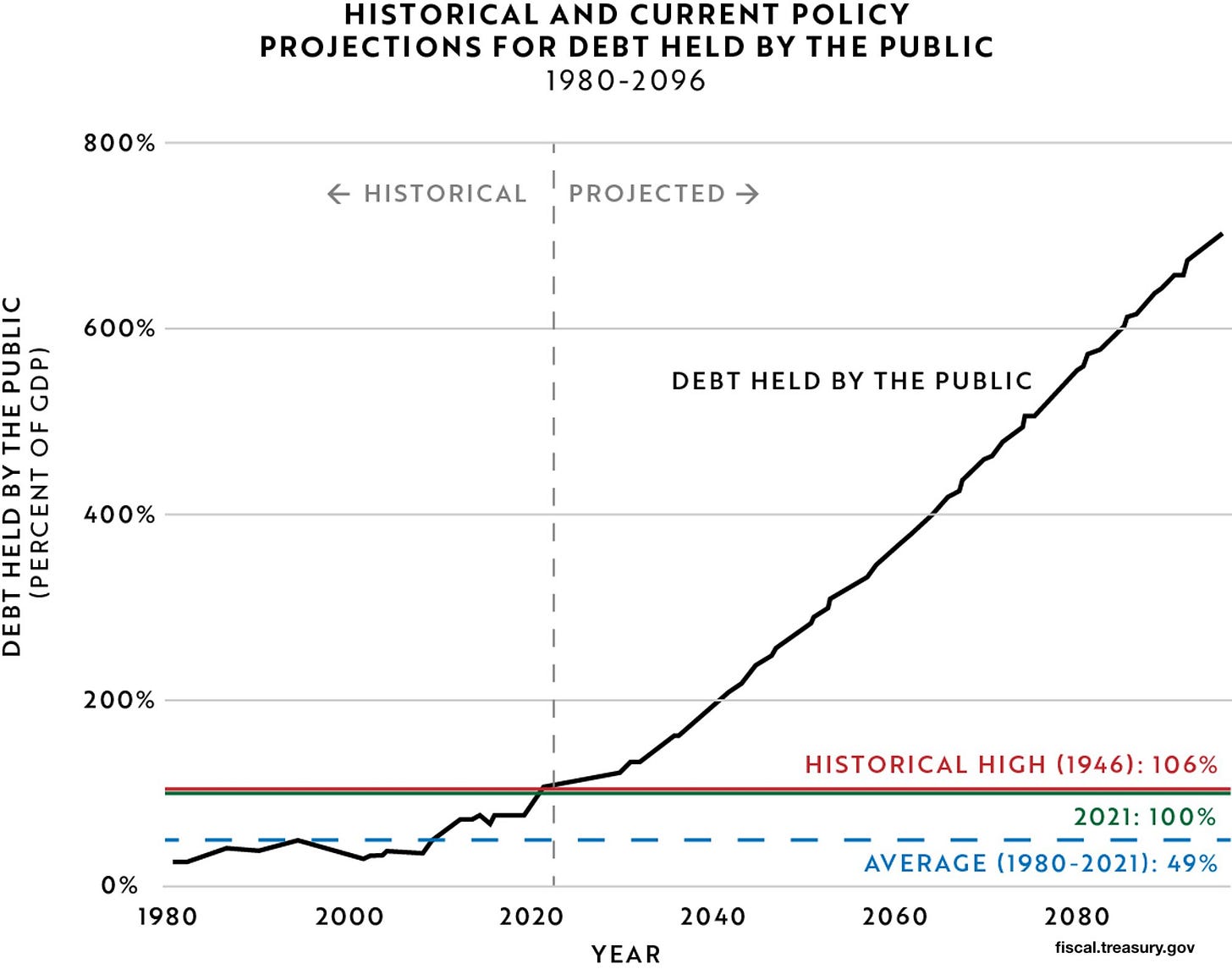

And so does the US Treasury Department (yes they actually published this):

On top of growing budget deficits that we cannot afford to pay, the US has $11T in debt due this year and next that must be refinanced.

Who’s going to fund that? The foreign sector is mostly interested in treasuries when the dollar is weak, which isn’t the case today.

The US has issued >$4T in treasuries to the public only once before (2021), and I find it hard to believe the Fed won’t need to step in and fund a significant portion. The CBO agrees, and projects QE will resume by 2026 (orange below). CrossBorder Capital, a leading research group focused on central bank liquidity, believes these estimates are too conservative and that the actual numbers will be closer to the grey bars below.

We’re also in the middle of a banking crisis…

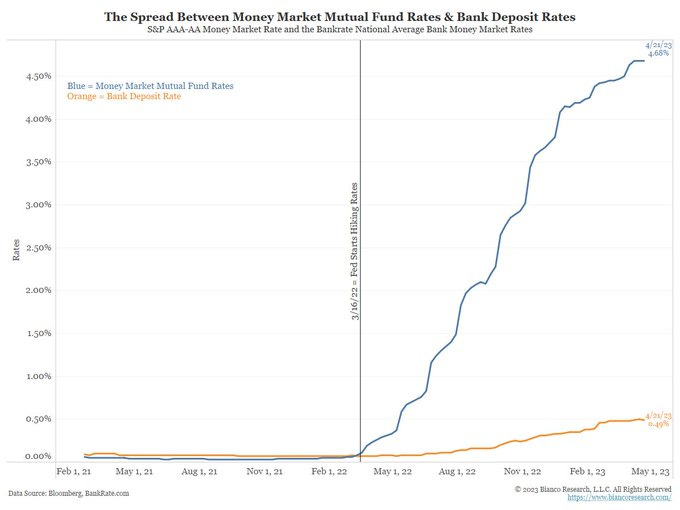

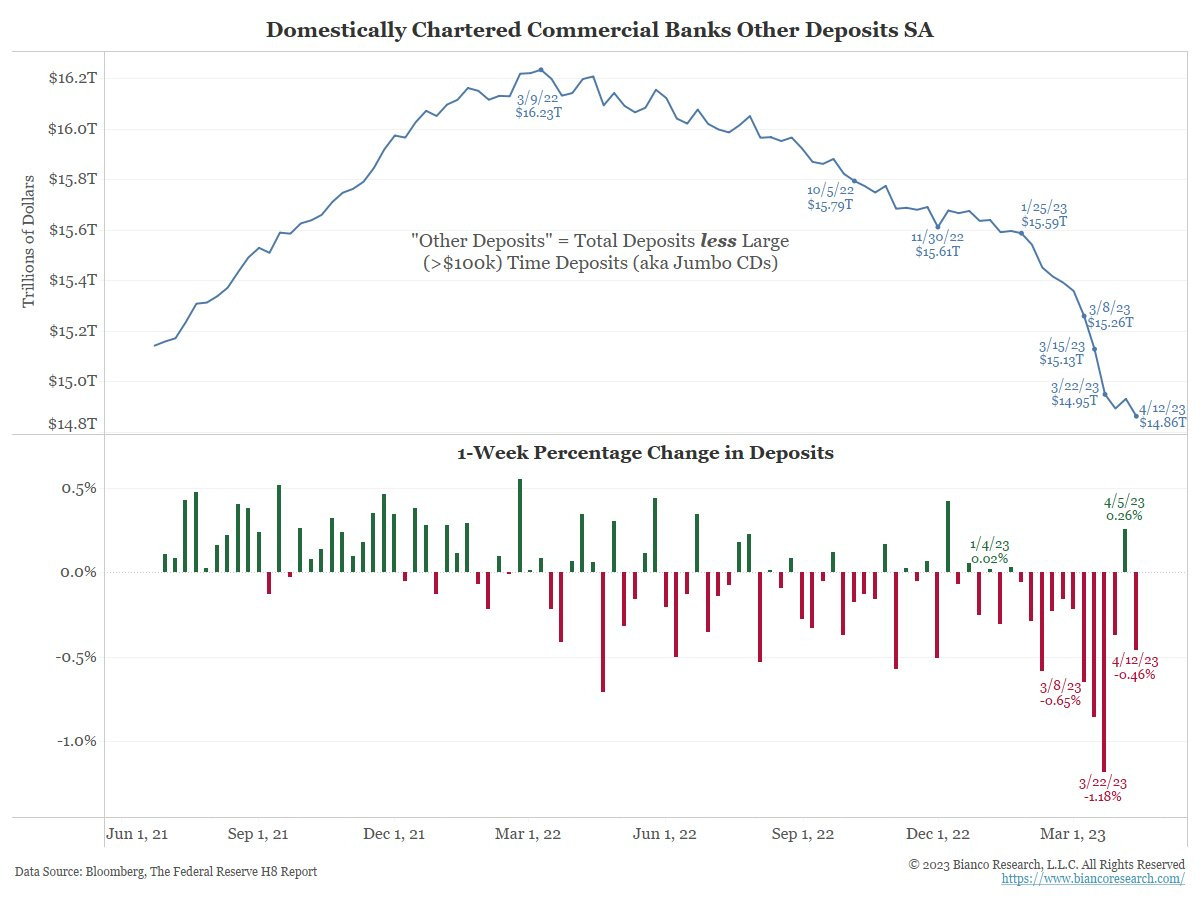

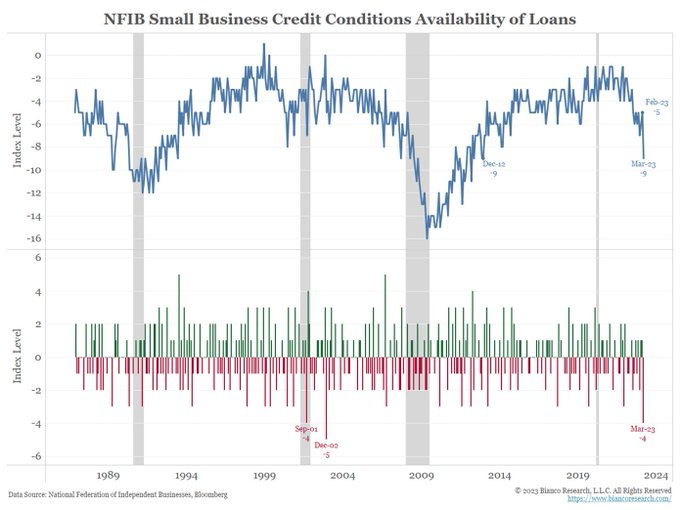

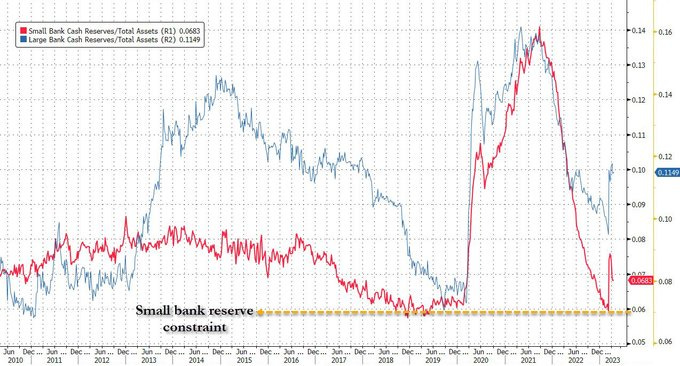

The Fed’s hawkish rate policy has had two major impacts on banks: declining balance sheet asset values and increasing spread between money market fund rates and bank deposit rates. The former was the culprit for the initial panic in March, which ultimately led to the demise of Silvergate, SVB, Signature, and most recently First Republic Bank. The latter is still playing out in real-time today.

Depositors can earn significantly more yield by transferring their money from banks to money market funds. This has caused a “bank walk”, lowering bank deposit balances, and ultimately limiting the banking sector’s ability to make loans.

When funding dries up, the economy slows down. This should become more apparent as the year progresses. With so much federal debt and mounting deficits, we cannot afford a significantly slowing economy.

The government stepped in with liquidity in the form of the BTFP in March of this year — they most likely will have to again if this situation continues to deteriorate.

What about the rest of the world?

The largest economies across the globe are also too levered and now facing similar bank collateral and federal interest expense issues as rates have risen sharply over the past year.

The second largest economy, China, also faces growth issues, with similar negative demographic dynamics. I find it hard to imagine a scenario for the global financial system, built on cheap debt, to continue operating without injecting more liquidity this year and next. Hopefully countries can gradually increase productivity and stimulate GDP growth through emerging technologies like crypto and AI — but that will take years. In the meantime, we, and the rest of the world, must continue to print.

I believe this inevitable trend will benefit crypto and tech stocks the most over the next few years.